- Dec 24, 2025

The Secret History of Old Master Sketchbooks

(reason #3 to keep a sketchbook - you'll be part of a conversation with artists who have been keeping sketchbooks through the centuries, and have a chance to explore their work and learn from them)

A sketchbook page by Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519)

I spent part of this month doing research for my upcoming Sketchbook Habit workshop, and wound up taking a deep dive into the history of sketchbooks, and the artists who kept them, and some of their stories, which are too good not to share. I read Walter Isaacson's biography of Leonardo da Vinci and discovered the sketchbook of Francesco de Giorgio Martini, had the chance to pick the brain of an art historian who told me the fantastic story of the practical joke John James Audubon played on Constantine Rafinisque, and had a chance to flip through the Codex Seraphinicus.

Chances are, the term "old master sketchbook" most likely conjures an image of one of the household names - Da Vinci's notebooks (above), or Delacroix's travel journals, but there are so many more artists out there who had incredible sketchbooks - here are a few of my favorites that are a bit more below the radar and not nearly as well known as they should be:

Villard de Honnecourt's medieval sketchbook (and cannabis and alcohol based painkiller recipe)

More than 300 years before the Renaissance, a 13th century french carpenter named Villard du Honnecourt filled his sketchbook with animals, people, cathedrals and "sound advice on the virtues of masonry and the uses of carpentry.", according to the first page of his book. Not all the pages survived the centuries, but there are still 33 pages of parchment remaining of his sketchbook, filled with over 250 drawings as well as his thoughts on architecture, descriptions of his travels to Hungary, and this recipe for a universal painkiller that features both cannabis and alcohol:

"Remember what I am about to tell you. Take leaves of red cabbage, and of avens – a herb called “bastard cannabis.” Also take a herb called tansy, and hemp, the seeds of cannabis. Grind equal amounts of these four herbs. Then take twice as much madder as any one of the four herbs, crush them, then put all five herbs in a pot and add the best white wine you can get to infuse it. Take care that the potion is not too thick to drink. Do not drink too much of it: a filled eggshell will be enough. This will heal whatever wound you might have."

The sketchbook of Villard de Honnecourt (early 13th century)

The Voynich Manuscript "The World's Most Mysterious Manuscript"

An unreadable text by an unknown artist in a nonexistent language, featuring astronomical chards, real and imaginary plants, naked women, and indecipherable pharmaceutical recipes, the Voynich manuscript has given headaches to countless linguists and cryptographers ever since it's discovery by Wilfrid Voynich, a rare books dealer, in 1915. There are theories that it's a complete guide to alchemy, which, when decoded, will reveal the secrets of the philosopher's stone, that it's an elaborate hoax, or a medieval pharmaceutical guide. It might be all of these things, but I'm convinced it's also a sketchbook - a glimpse into a curious mind at work, determined to interpret reality and create it's own.

Voynich manuscript (early 15th century)

The Sketchbook that Inspired Leonardo da Vinci: the architectural sketches of Francesco de Giorgio Martini

Francesco de Giorgio Martini was known as "the Leonardo of Siena", and was one of the great Renaissance polymaths - he was a painter, sculptor, writer, architectural theorist and hydraulics expert. His sketchbook, which has remained intact, has more than 1200 drawings - it's a log of his architectural projects and designs for buildings as well as catapults and trebuchets to be used in times of war. He was about 20 years older than Leonardo da Vinci, who admired and owned a copy of his architectural sketchbook, and met him when they were both hired to consult on the design of the cathedral in Milan. Da Vinci actually wrote the Milanese authorities a request asking for Giorgio Martini to accompany him on a trip to Pavia to look at the cathedral there. It was in the castle in Pavia that they discovered a copy of a manuscript by Vitruvius which led them both to create a drawing of the Vitruvian man.

The architectural sketchbook of Francesco de Giorgio Martini (1439-1501)

The Tree Sketchbook of Fra Bartolommeo

This sketchbook by Fra Bartolmmeo della Porta contains 43 drawings of trees and landscapes, and is one of the first significant bodies of plein air drawings in existence. These trees don't appear in his paintings, and weren't done for sale (the order Fra Bartolommeo belonged to actually forbade him receiving money for artwork). He made this during his travels around Tuscany purely for the pleasure of being with and amongst trees. Each drawing feels like both a study and a portrait of a tree, his attempt to understand it and to capture it's essence.

A sketchbook drawing by Fra Bartolommeo (1472-1517)

If you're interested in learning to draw trees, here's a workshop I put together based on everything I've learned from the old masters, as well as the last 10 years of my own tree drawing project:

The Teen Goth Sketchbook of Peter Paul Rubens

When he was in his early teens, the young Peter Paul Rubens fell in love with Hans Holbein's "The Dance of Death" - a hugely popular series of woodcuts which had gone through multiple editions by the time Rubens saw it (some of the copies that still exist today are bound in human skin). The 12 year old Rubens filled a sketchbook with his copies and interpretations of the woodcuts - this was a way of learning from, and having a conversation with, an artist that he admired, improving his skills, and, possibly, finding a way to grapple with the questions of mortality and impermanence that many teenagers struggle with.

The childhood sketchbook of Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640)

The Travel Sketchbooks of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot

Corot travelled constantly over the course of his career, taking inspiration both from the changing European landscape and the work he saw by other artists. He explored France extensively, travelled through Holland and Belgium took several long, formative trips to Italy to study the Italian renaissance masters and spend time with other young landscape painters (there are pages from his italian sketchbooks drawn by his friends). He filled over 80 sketchbooks with his travel itineraries, notes and quick, gestural graphite drawings.

A sketchbook by Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot (1796-1875)

The Alpine sketchbooks of John Singer Sergeant

John Singer Sargeant never had much formal education. This was partially due to his parent's itinerant lifestyle (his mother was notoriously restless, moving the family every few months for reasons that ranged from the desire to meet with other expat families, her anxiety over a potential cholera outbreak, or simply the desire to wake up somewhere new), as well as his own temperament - as a child, he had a difficult time sitting still unless he was drawing. His mother encouraged him and his sister Emily to sketch from life while they travelled. The alpine sketchbooks are filled with plein air paintings from a family trip through the alps taken when Sargeant was 14 years old.

A page from one of the Alpine sketchbooks of John Singer Sargeant (1856-1925)

The Latin Grammar Textbook of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

This is the old school textbook of Henri de Toulouse Lautrek - he was 16 years old when he needed to take a mandatory Latin class, and seems to have spent most of his time in class doodling on the margins of his grammar book. There are over 400 tiny ink drawings in this book, of everything from his classmates and teachers, to horses and the pierrot on a gallows, below - the latter seems to be a warning to anyone who might borrow the book and not return it - the text under it reads: "Look at Pierrot hanged, who did not return the book; if he returned it, he would not have been hanged.".

Somewhat unsurprisingly, Toulouse Lautrek failed his Latin exam the first time he attemted to take it, although he passed on the second attempt the following year.

A page from the Latin textbook of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901)

The field sketchbook of Constantine Rafinisque full of creatures made up by John Audubon

Constantine Samuel Rafinisque was a french naturalist who filled his sketchbooks with field notes about the plants and animals he was studying. He visited the united states and sought out John James Audubon, staying with him for 8 days in search of information about new species. At some point of the visit he destroyed audubon's favorite violin and presumably trashed his house while attempting to kill a bat, which he was convinced was a new species. Here is Audubon's description of the incident:

"I heard a great uproar in the naturalist's room. I got up, reached the place in a few moments, and opened the door, when, to my astonishment I saw my guest running about the room naked, holding the handle of my favourite violin, the body of which he had battered to pieces against the walls in attempting to kill the bats which had entered the open window, probably attracted by the insects flying around his candle. I stood amazed, but he continued jumping and running round and round, until he was fairly exhausted: when he begged me to procure one of the animals for him, as he felt convinced they belonged to 'a new species."

Possibly as revenge for his violin, Audubon proceeded to give Rafinisque detailed descriptions of multiple species of animals he claimed to have seen during his nature walks, which Rafinisque faithfully documented in his sketchbooks and which weren't discovered to be fake until fairly recently. These included the imaginary rodents on the page below (a Big-Eye Jumping Mouse, bottom left, a Three-Striped Mole rat, top left, and a Lion-Tail Jumping Mouse which posessed eyes the size of large marbles, ears that rival a rabbit’s, and massive hind legs and paws.") as well as a 10 foot long fish with bulletproof scales.

A page from the field sketchbook of Constantine Samuel Rafinisque (1783-1840)

The Strangest Book Ever Published: The Codex Seraphinicus

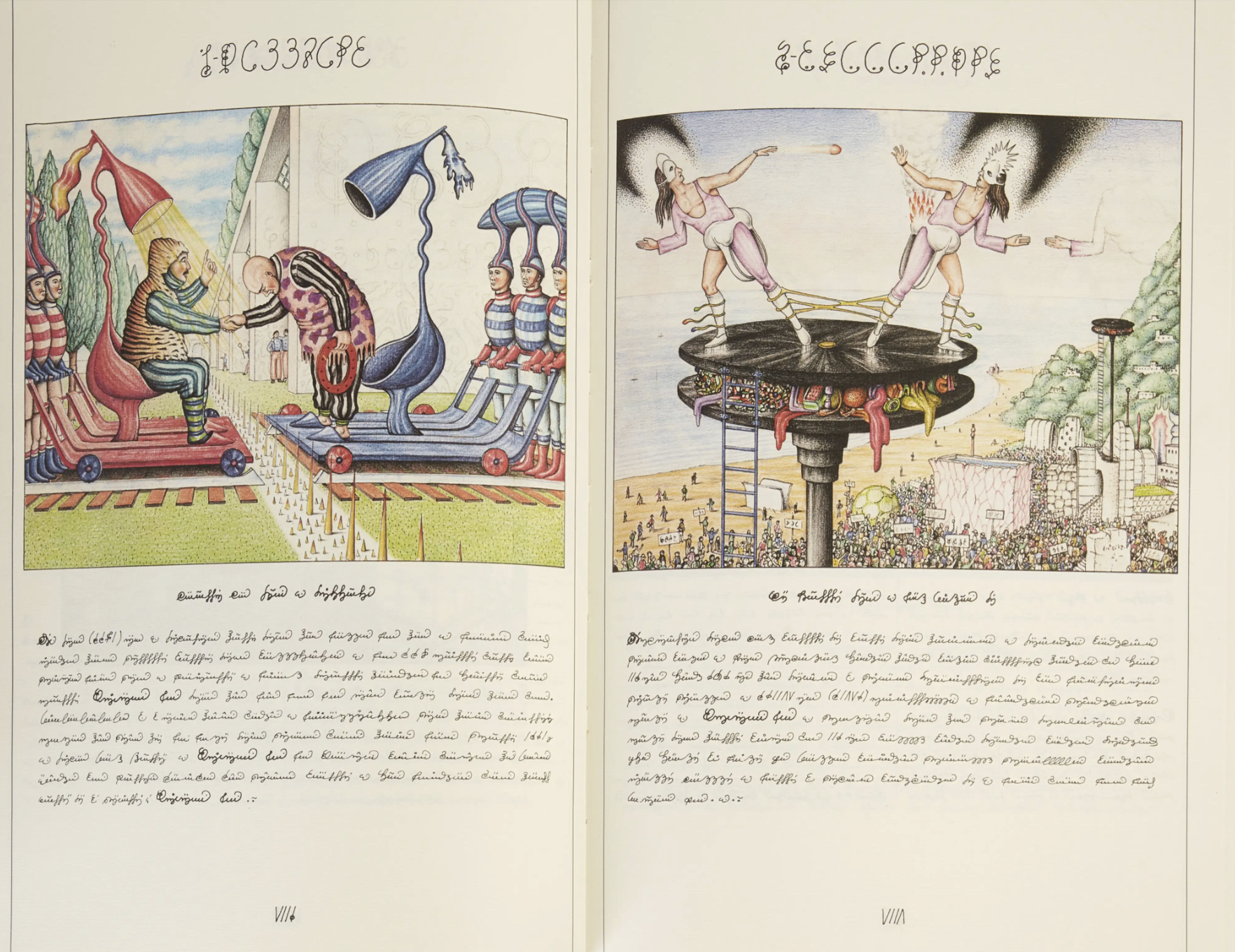

Much like the Voynich manuscript, the Codex Seraphinicus - written in an incomprehensible language, illustrated with drawings of an alien world adjacent to, and occasionally overlapping with our own - has never been decoded. However, we know exactly who the author is - moreover, he's still alive. The creator of the codex, Luigi Serafini, is convinced that the text will never be decoded since it means nothing (which doesn't stop the book's cult fanbase from trying to break the code).

The drawings in the book are beautifull, bizarre, puzzling, funny - at it's core though, I consider this book a type of sketchbook - a documentary of the author's internal landscape, not meant for anyone except him to understand.

A page from the Codex Seraphinicus by Luigi Serafini (1949-present)

The rest of the sketchbooks I found made their way into my Sketchbook Habit workshop. If you are interested in beginning your own sketchbook, and want to build a solid foundation for your sketchbook habot, you can download the free guide with tips and advice that I made at the bottom of the page below, or sign up for the class:

Dina Brodsky

"I believe that the act of keeping a sketchbook journal has been one of the most important decisions I have taken in my life as an artist. My sketchbooks are the heart of my studio practice, my travel companions, my place to play and explore. They have served as a way of developing my skills, and a method of examining my life, the place where I discovered who I was, and created the person I wanted to be. I’ve kept sketchbooks consistently for almost 25 years, and during that time they’ve provided a sanctuary when I needed a place to retreat, and catharsis when I needed change.I want to share everything I’ve learned throughout my sketchbook practice, to explore the universe of artist sketchbooks, and to help others develop a sketchbook practice of their own."